Scroll down for English version

Lino Tagliapietra. La danza del fuoco

Da Murano a Seattle. Vita e arte di un grande maestro del vetro veneziano

di Micaela Zucconi

Occasione di questo incontro con il maestro Lino Tagliapetra è stata l’inaugurazione della mostra “Lino Tagliapietra. Glasswork” a Punta Conterie, a Murano, nel settembre del 2019. Uno spazio dedicato all’arte in una parte di quelle che erano le fabbriche dove si producevano le perle di vetro – le conterie per l’appunto – ricavate da canne di vetro

forate.

Un’esposizione di 65 opere, molte create per l’occasione, allestita nella natia e mai dimenticata Murano.

Dopo i primi passi della carriera in laguna, il maestro ha attraversato l’Oceano approdando a Seattle. Qui si trova il suo studio ove ancor oggi, a 87 anni, sperimenta, crea, insegna e condivide, con allievi e studiosi, la sua conoscenza tecnica e artistica. Con la modestia dei grandi personaggi, Tagliapietra non ama definirsi un artista

Ho un concetto un po’ francese del lavoro, ho un po’ di pudore. Cerco di produrre bellezza…

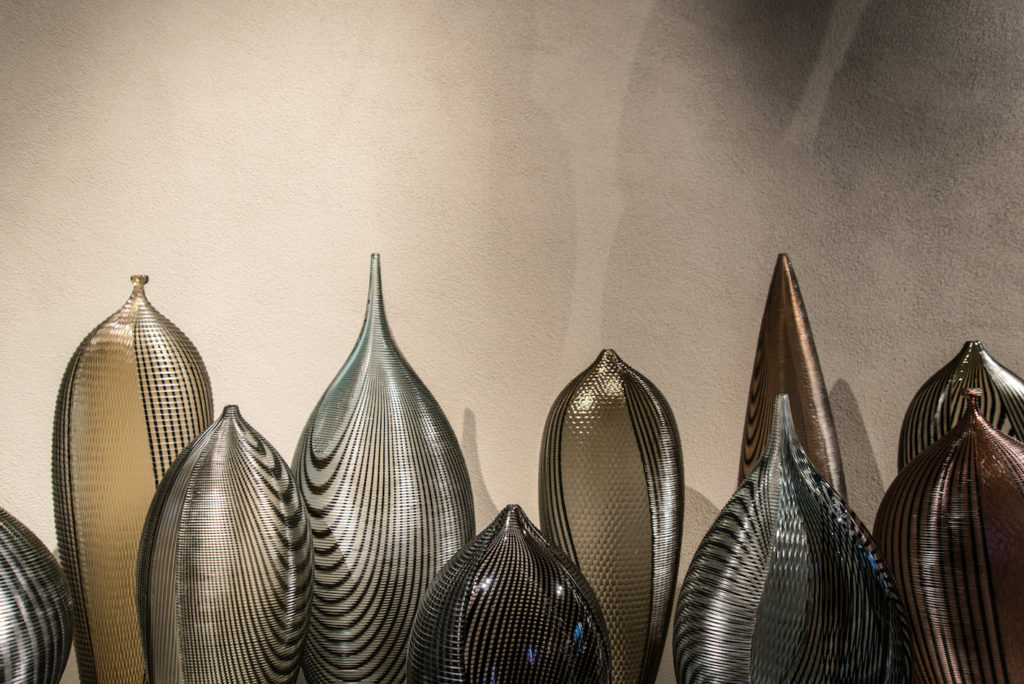

- Dinosauri ; ph : Valentina Cunja

Le sue opere hanno influenzato radicalmente il vetro muranese e non solo. Passeggiando sotto l’installazione Ali di vetro – leggiadri gabbiani – tra 50 piccole forme in vetro avventurina (una pasta di vetro cristallina traslucida con cristalli di rame brillanti), Dinosauri dai colli flessuosi e molte altre creazioni vibranti di colore, il maestro racconta i suoi esordi.

“Ho iniziato a lavorare in fornace a 11 anni, alla fine della Seconda Guerra Mondiale.

Si lavorava tantissimo, la fabbrica straripava di gente.

Ho imparato piccole cose e mi sembrava di essere bravissimo. Invece…

Dopo il servizio militare ho trovato un maestro.

Giovanni – Nane – Ferro, chiamato Catari, che mi ha insegnato ad avere pazienza con me stesso.

Era molto credente, prima di lavorare si pregava.

Utilizzava le tecniche più tradizionali, con lui ho appreso molto.

Se vuoi imparare a soffiare il vetro sono necessari dai cinque ai sette anni.

Poi, se vuoi diventare bravo, ci vuole tutta la vita”.

- Ali in vetro ; ph : Valentina Cunja

Lino Tagliapietra ricorda quando era ancora un giovane apprendista da Archimede Seguso. Tanta ricerca, il fervore prima delle Biennali, per realizzare oggetti d’arte. Le fornaci importanti partecipavano, tra queste anche Venini e Barovier & Toso.

“Ho visto fare cose stupende”.

A 21 anni Tagliapietra è già un giovanissimo maestro vetraio. Un ricordo di quel periodo in particolare?

“Sarà stato il 1964.

Studiavo molto le tecniche dei vetri romani e avevo realizzato una forma

particolare, una specie di semisfera in vetro soffiato per partecipare alla mostra di San Nicolò, a Murano.

In molti non capivano come fossi riuscito a farla.

Ricordo l’emozione quando Luigi Zecchin, massimo studioso del vetro muranese, affermò che nella storia del vetro quella forma non era stata mai fatta prima”.

All’epoca il pezzo era stato venduto per circa mille lire.

“Ho tentato di riaverlo offrendo 15 mila euro, ma non vogliono venderlo. L’ho rifatto, ma non mi ha dato la stessa emozione”.

Il 1979 è l’anno del cambiamento. Per la prima volta in America, Tagliapietra insegna alla Pilchuk Glass School, a Seattle, che diventerà la sua seconda casa. Nella città sulla costa occidentale degli Stati Uniti, al primo studio ne segue un secondo negli anni Novanta. Un luogo di lavoro e ricerca, con una splendida galleria d’arte, ristrutturato nel 2017 da Graham Baba Architects.

Nei suoi 70 anni di attività Tagliapietra, pur restando vicino alla tradizione, ha giocato con una libertà espressiva scevra dai canoni più classici. Al suo fianco, da oltre 60, la moglie Lina, di cui si è innamorato a 17 anni.

“Lei ne aveva 16, una grande compagna, che ha saputo sempre aspettarmi e comprendere gli umori di uno che lavora.

Quando sono andato a parlare con suo padre, uomo che ho stimato moltissimo, mi ha detto: ‘Cosa vuole che le dica? Buona fortuna’. E ne abbiamo avuta nella vita e nel lavoro.”

Pluripremiato, Tagliapietra ha esposto e continua a esporre, senza fermarsi. Le sue opere dai colori vibranti, con forme frutto di un virtuosismo che gli consente ogni possibile e incredibile acrobazia tecnica, vengono accolte nei musei di tutto il mondo. Dal De Young Museum di San Francisco al Museo del Vetro di Murano, dal Victoria & Albert di Londra al Musée des Arts Décoratifs di Parigi e al Metropolitan Museum di New York, oltre che in gallerie e collezioni private.

- Giudecca ; ph : Valentina Cunja

Tagliapietra, figura chiave nel mondo del vetro, riveste un ruolo di enorme importanza anche per il suo impegno nella trasmissione del sapere. Non si contano i corsi e gli workshop tenuti dal maestro. Molti suoi allievi, e ce ne sono decine, sono diventati artisti affermati.

Cosa consiglierebbe ai giovani che vogliono accostarsi a quest’arte?

“Devono imparare a sacrificarsi.

Il vetro dà stimoli immediati e belli, ma devi avere pazienza e amare questo lavoro.

Il vetro è cultura e tecnica, è collegato con l’arte. Anche a quella contemporanea, che può essere di ispirazione.

Gli artisti del vetro americani contemporanei guardano alla cultura europea”.

Come dimostrato anche nell’ambito della recente edizione de Le Stanze del Vetro della Fondazione Giorgio Cini (Gennaio 2021), dedicata a “Venezia e lo Studio Glass americano”, che ha messo in luce la varietà dell’arte e del design nel vetro oltreoceano.

Si studia abbastanza il vetro in Italia?

“In Germania, Belgio e Francia studiano molto più di noi il vetro antico e romano.

Mi piacerebbe che si riuscisse a sviluppare un grande museo e centro di ricerca”.

Che progetti ha il maestro per il prossimo futuro?

“Ne ho molti, ma il tempo corre veloce.

Mettere queste idee sulla carta non è nelle mie corde. È tutto nella testa. Ho bisogno di lavorare.

Rimango muranese, ma cerco di camminare al passo coi tempi”,

specifica Tagliapietra, che ora trascorre mediamente sei mesi nel corso dell’anno nella sua isola natale, dove ha un’altra base, il Murano Studio Glass.

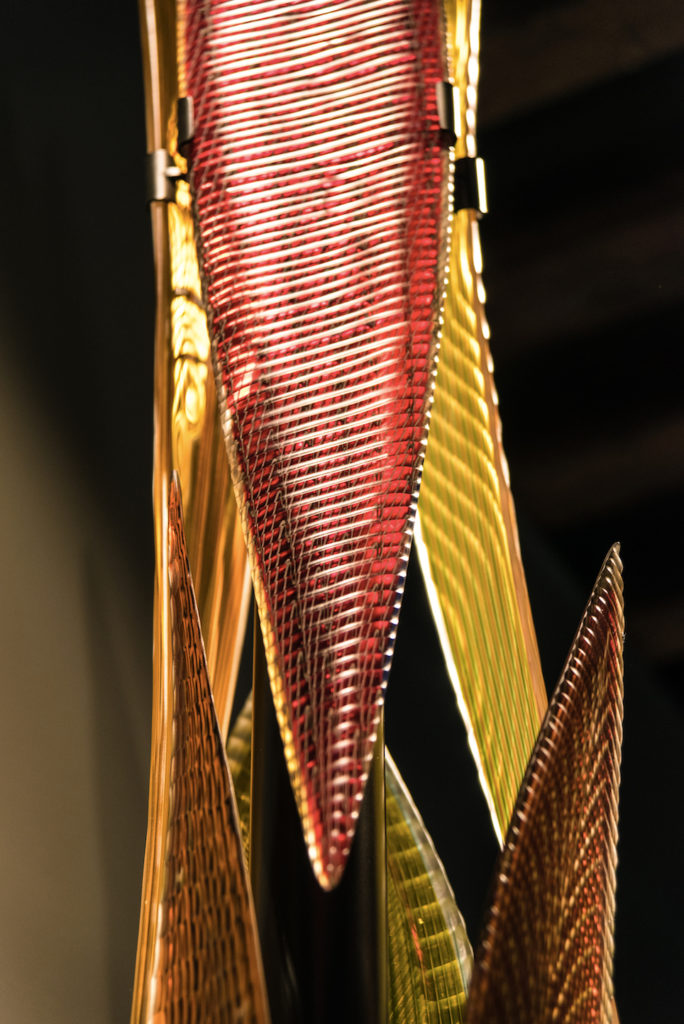

- Serie pannelli Venezia ; ph : Valentina Cunja

“Cosa mi piacerebbe fare?

Cose nuove, con colori semplici e tecniche un po’ rivoluzionarie, da sviluppare”.

Ma cosa si può ancora inventare?

Dobbiamo ancora cominciare.

- Lino in conversation with Micaela ; ph : Valentina Cunja

puntaconterie.com

linotagliapietra.com

***

Lino Tagliapietra. The dance of fire

From Murano to Seattle. The Life and Art of a great Venetian Glass Master

by Micaela Zucconi

The occasion of this meeting with The Master Lino Tagliapetra was the opening of the exhibition “Lino Tagliapietra. Glasswork” in Punta Conterie, Murano, in September 2019. A space dedicated to art in a section of a building that used to host the factories where glass beads — the conterie — were made from perforated glass rods.

An exhibition of 65 works, many created for this particular occasion, set up in his native and never forgotten Murano.

After the first steps in his career in the Venetian lagoon, the maestro crossed the ocean and landed in Seattle. There, he has his studio where even today, at the age of 87, he experiments, creates, teaches and shares his technical and artistic knowledge with students and scholars alike. With the modesty typical of outstanding figures, Tagliapietra does not like to call himself an artist:

I have a somewhat French concept of work, I have a bit of modesty.

Mine is an attempt to produce beauty…

His works have radically influenced glassmaking in Murano and beyond. Strolling underneath the installation Ali di vetro (Wings of glass) — graceful seagulls — among 50 small shapes of aventurine glass (a translucent crystalline glass paste with brilliant copper crystals), Dinosaurs with sinuous necks and many other vibrant coloured creations, the master recounts his beginnings.

“I started working at the furnace at 11, at the end of the Second World War.

We worked a lot, the factory was crowded with people.

I learned little things and I felt like I was very good.

However… After military service I found a teacher. Giovanni — Nane — Ferro, known as Catari, who taught me to be patient with myself. He was a man of great faith. Before starting to work we would pray.

He used the more traditional techniques. I learned a lot from him. If you really want to learn how to blow glass, it takes five to seven years. Then, if you want to become great at it, it takes a lifetime.”

- Masai ; ph : Valentina Cunja

Lino Tagliapietra recalls the time when he was still a young apprentice to Archimede Seguso. A lot of research, the excitement before the Biennials, to create art objects.

Prominent furnaces participated in the exhibitions with their creations, including Venini and Barovier & Toso.

“Back then, I saw wonderful things.”

At the age of 21, Tagliapietra was already a very young master glassmaker. A specific memory of that period?

“It must have been 1964.

I studied the techniques of Roman glassmaking a lot and I had created a particular shape, a kind of blown glass hemisphere to participate in the San Nicolò exhibition in Murano.

Many did not understand how I managed to do it. I still remember my emotion when Luigi Zecchin, the greatest scholar of Murano glass, said that in the history of glass that shape had never been made before.”

At the time, the piece was sold for about a thousand lira.

“I tried to get it back by offering 15 thousand euros, but the owners don’t really want to sell it.

So I made another one for myself, but it didn’t give me the same thrills.”

1979 was the year of change. For the first time in America, Tagliapietra became a teacher at the Pilchuk Glass School, in Seattle, a place that would go on to become his second home. In the city on the west coast of the United States, the first studio was followed by a second one in the 1990s. A place of work and research, with a splendid art gallery, renovated in 2017 by Graham Baba Architects.

In his 70 years of activity, while remaining true to tradition, Tagliapietra has played with expressive freedom, away from the most classic canons. By his side, for over 60 years, there has been his wife Lina, with whom he fell in love at the age of 17.

“She was 16, a great partner who was able to wait for me and understand the moods of someone working like me. When I went to talk to her father, a man I highly esteemed, he said to me: ‘What do you want me to tell you? Good luck’.

And I must say that we have had it in the private as well as professional life.”

A multiple award winner, Tagliapietra has never stopped to exhibit his creations.

His vibrantly coloured works–with shapes that are the result of a virtuosity that allows him to perform all possible and incredible technical acrobatics–are welcomed in museums all over the world. From the De Young Museum in San Francisco to the Murano Glass Museum, from the Victoria & Albert Museum in London to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris and to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, as well as galleries and private collections.

- Endeavor Art Installation @ Punta Conterie ; ph : Valentina Cunja

Tagliapietra, a key figure in the world of glass, plays a hugely important role, in particular for his commitment to the transmission of knowledge. As a teacher, he has held countless courses and workshops. Many of his students, and there are dozens of them, have became established artists.

What would you recommend to young people who want to approach this art?

“They should learn to sacrifice themselves.

Glass can immediately give you great thrills, but you have to be patient and love this job.

Glass is a combination of culture and technique, it is connected with art, even contemporary, which can be inspiring.

I should also say that women often perform much better than men.

Their bodies are less strong, but they make up for it through technique.

Nancy Callan, for example, has these characteristics.

Contemporary American glass artists look to European culture.”

It was also demonstrated in the recent edition of Le Stanze del Vetro by the Giorgio Cini Foundation (January 2021), dedicated to “Venice and the American Glass Studio,” which highlighted the variety of art and design in overseas glassmaking.

Is glassmaking studied enough in Italy?

“In Germany, Belgium and France they study ancient and Roman glassmaking much more than we do.

I would like a large museum and research centre to develop anytime soon.”

Maestro, what plans do you have for the near future?

“I have many, but time flies.

Putting these ideas on paper is not my thing. It’s all in my head. I need to work.

I still am a Muranese, but I try to keep up with the times”, says Tagliapietra, who now spends about six months a year on his native island, where he has another base, the Murano Studio Glass.

- Reticello with Murano canal in the background ; ph : Valentina Cunja

“What would I like to do?

New things, with simple colours and somewhat revolutionary techniques, still to be developed, though.”

But what can still be invented?

I guess we haven’t started yet.

- Lino Tagliapietra @ Punta Conterie