Scroll down for English Version

Vetro e Disegno, il processo creativo nelle storiche vetrerie muranesi del ‘900 * — in mostra a InGalleria / Punta Conterie Art Gallery a Murano fino al prossimo 19 luglio — è il progetto espositivo a cura di Caterina Toso, storica del vetro ed erede dell’Archivio della Fratelli Toso, dedicato a ripercorrere decennio dopo decennio Murano in quello che è stata nel secolo scorso: una fucina di idee, di arte, di innovazione ma anche straordinario e operoso hub produttivo e commerciale su scala internazionale.

Attualmente chiuso al pubblico per l’emergenza sanitaria Covid-19, Vetro e disegno ha rappresentato il pretesto per dare il via ad una conversazione con Caterina Toso tra vetro di ieri e di oggi in una Murano in evoluzione. Un primo capitolo che contiamo di arricchire con ritmo nelle prossime settimane, mesi.

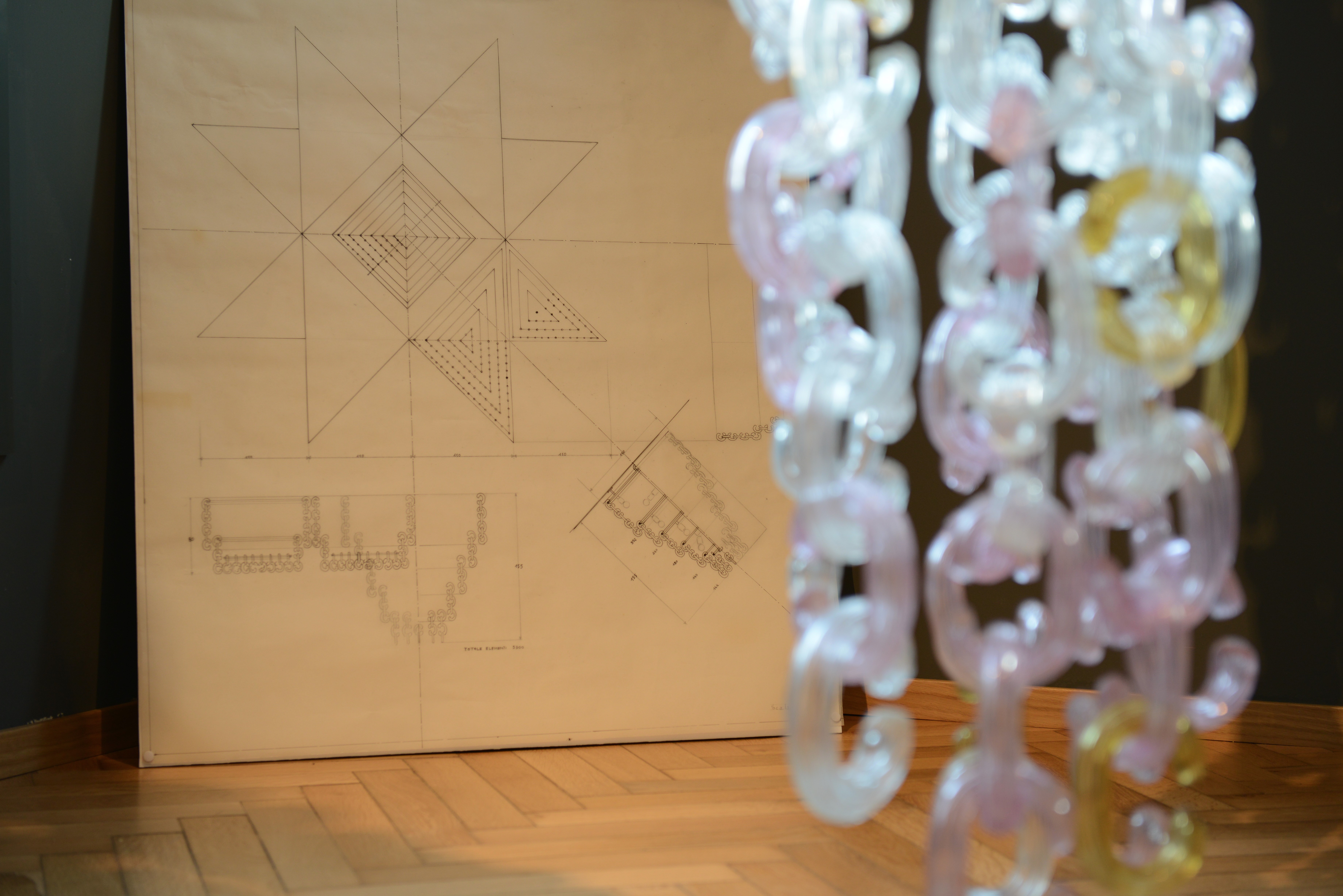

Vetro e disegno, ph. Valentina Cunja

Vetro e disegno è un progetto focalizzato sulla produzione vetraria a Murano nel secolo scorso ma del tutto attuale vista la natura dei manufatti in mostra. Ancora oggi infatti la realizzazione di un vetro artistico passa attraverso il dialogo tra Maestro e designer, un rapporto non sempre facile, spesso — ho notato che non smetti mai di sottolinearlo — determinato dalla mancanza di conoscenza del mondo del vetro e delle sue tecniche da parte dei designer.

Ætemporary — Visitando la mostra appare chiaro che la visione di un creativo ha indotto a sperimentare con tecniche e colori in maniera inedita, spingendo lo stesso Maestro a forzare la mano. Alcuni pezzi in mostra sono rappresentativi dell’importanza e del potenziale di questo sodalizio. Vuoi approfondire alcuni esempi? Ci sono ad esempio pezzi che non potrebbero più essere riprodotti, per fattori dettati dal caso, da colori e finiture realizzati con composti che oggi non si possono più usure. Qualche esempio?

Caterina Toso — Tutte le opere selezionate per questo percorso sono il risultato dell’interazione tra la creatività del disegnatore/ artista/architetto e la mano del maestro: solo mettendo in collaborazione e facendo interagire questi due aspetti in maniera oliata possono nascere delle opere d’arte. La mano del maestro permette all’ingegno ed alla fantasia del creativo di prendere forma nella materia; dall’altra parte la creatività dell’artista suggerisce al maestro l’uso diverso ed innovativo di colori, forme, tecniche aggiungendo importanti elementi di ispirazione artistica.

Credo che questo principio sia particolarmente evidente nelle opere disegnate da Dino Martens per la vetreria Aureliano Toso: l’uso di colori e tecniche della tradizione fusi e mescolati in maniera apparentemente casuale – il risultato sono dei vetri colorati, brillanti, moderni. Elementi della tradizione stravolti e decontestualizzati. Alcuni dei colori che possiamo ammirare in queste opere non sono più riproducibili oggi a causa di divieti e limitazioni sull’uso di elementi e composti chimici classificati come tossici. Molte tecniche che venivano padroneggiate con disinvoltura, se non perdute completamente, oggi non trovano degli esecutori altrettanto abili. Va sottolineato che questo dipende non tanto da una mancanza odierna di talento, quando più dalla quotidianità del lavoro di un tempo: la ripetitività quotidiana di gesti, manovre, lavorazioni (5-6 giorni la settimana, più di 8 ore al giorno a partire già da giovanissima età) permetteva ai maestri di un tempo di acquisire livelli tecnici talmente elevati da arrivare a riprodurre con semplicità risultati molto complessi.

Oriente Osellare Congo Vetreria Aureliano Toso, Dino Martens, 1952

Æ — Spostando il ragionamento dalla mostra ad oggi, ritieni che il mondo del design — o se vogliamo del progetto — possa rappresentare un plus per il vetro di Murano?

CT — Si, potrebbe. Senza voler generalizzare credo che spesso l’arte vetraria muranese contemporanea rimanga schiacciata sotto il peso della storia e della tradizione; fatica a liberarsi da forme e stili talmente tradizionali da risultare stantii. Il design potrebbe di certo portare un influsso di novità e creatività, di idee nuove che gioverebbero alla produzione artistica. Il problema sta nella mancanza di interazione tra la parte creativa e quella produttiva: il designer spesso non si prende la briga di entrare in sintonia confrontandosi con la parte produttiva. Il progetto è effettivamente realizzabile in vetro? Potrebbero essere raggiunti risultati più interessanti, artisticamente e – perché no – anche commercialmente, apportando delle modifiche (suggerite da chi la materia la conosce come le proprie tasche?). I maestri non sono dei meri esecutori, ma degli interpreti. D’altra parte i maestri dovrebbero capire che non sempre “foresto” è male, che la contaminazione di idee provenienti dall’esterno sono necessarie e fisiologiche per sopravvivere ed evolversi. Rispettare la tradizione significa anche permetterle di crescere grazie all’esperienza degli altri.

Rispettare la tradizione significa anche permetterle di crescere grazie all’esperienza degli altri.

Vetro e disegno, ph. Roberta Orio

Æ — Se sì, come fare per avvicinare questo mondo a Murano in maniera costruttiva?

Residenze, workshop formativi potrebbero essere un’occasione utile per colmare il gap alla base andando a formare una nuova generazione di creativi a loro agio con il mondo del vetro di Murano? Se si, un esempio che ritieni utile condividere?

CT — Passaggio generazionale credo sia il termine chiave. Bisogna accettare che i modelli del passato non sono eterni, anzi: “affinché una tradizione si mantenga viva, deve essere continuamente reinventata” (cit. Olivier Brault, Direttore Generale della Fondation Bettencourt Schueller).

Murano dovrebbe formare una nuova generazione di maestri, muranesi e di qualsiasi altra provenienza: maestri abili con le mani, grazie alla secolare scuola di lavorazione locale, ma anche aperti di mentalità. Artisti-artigiani a tutto tondo, educati alla conoscenza e al rispetto della tradizione ma proiettati verso il futuro, in grado di interagire ben oltre i confini locali, capaci di assorbire positivamente idee e influenze internazionali, anche le più moderne e tecnologiche che non devono essere viste come distorsioni pericolose ma come preziose opportunità.

Æ — Azioni di questo tipo hanno un valore più ampio che va ben oltre la mera produzione potenziando il lato attrattivo di Murano verso un pubblico e un turismo colto che è poi quanto si propone di fare Punta Conterie, lo spazio che ospita Vetro e disegno fino al prossimo luglio. Cosa ne pensi?

CT — Io credo che il futuro di Murano, come della nostra vicina Venezia, sia la cultura. Oggi più che mai dobbiamo ripensare la nostra isola in funzione di un turismo culturale, interessato e attratto da un’offerta calibrata sull’alta qualità.

Punta Conterie, ph. Maris Croatto

Æ — Dialogando di vetro non esclusivamente con addetti del settore, ho spesso la percezione che il vetro non venga percepito come materia legata alla contemporaneità. La tradizione arriva prima. Da una parte è senza dubbio un bene perché rafforza il lungo legame e la straordinaria specificità di Murano nel dominare il vetro, dall’altra però rischia di non trovare un canale di dialogo con i più giovani o con una platea più ampia stimolata dalla novità. Da Muranese appartenente ad una delle grandi famiglie e imprese del settore nonché grande conoscitrice degli archivi storici, cosa ne pensi?

CT — Credo di aver risposto a tratti nelle domande precedenti.

Æ — Forse bisognerebbe investire di più nel rafforzare la cultura del vetro contemporaneo con l’apertura di luoghi dedicati, Musei, gallerie sul modello di quanto accade in molti altri paesi a livello mondiale?

CT — Sicuramente. L’arte del vetro muranese si deve rinnovare a 360°: questo non vuol dire dimenticare o tradire una secolare tradizione, ma significa prendere il nostro ricchissimo bagaglio culturale e renderlo fruibile in maniera moderna, interattiva. Deve scrollarsi polvere e odore di naftalina di dosso, veicolando la sua storia in modo da raggiungere le nuove generazioni a cui spetterà il compito di portare avanti la tradizione e l’arte vetraria nel futuro.

Æ — Ripristinare — come ritiene Lino Tagliapietra, il più importante artista del vetro noto a livello mondiale — la Biennale del Vetro potrebbe essere utile per riportare l’attenzione sul vetro artistico?

CT — Qualsiasi manifestazione inclusiva e rappresentativa, che dia spazio alla tradizione, alla modernità, all’interazione tra la scuola locale e quelle internazionali. Che dia spazio ai “big” come anche ai giovani emergenti. Dove venga data ugual attenzione alla parte esecutiva – al maestro – e alla parte creativa e progettuale – disegnatore.

______________

* Vetro e Disegno, il processo creativo nelle storiche vetrerie muranesi del ‘900 presenta disegni e oltre 50 vetri artistici realizzati tra gli anni ’10 e gli anni ’80 del ‘900, provenienti, così come il materiale d’archivio esposto, delle vetrerie di Fratelli Toso, Barovier&Toso , SALIR , A.Ve.M e Galliano Ferro e dalla Fondazione Giorgio Cini e il Centro Studi Vetro con i disegni di Venini, Seguso Vetri d’Arte e Aureliano Toso. Le opere, tutti vetri originali, provengono da importanti collezioni private italiane e straniere, tra cui la collezione Holz del tedesco Lutz H. Holz e degli eredi Vistosi.

Vetro e disegno

***

Glass and design, the creative process in the historic Murano glass factories of the 20th century * — the exhibition hosted at InGalleria / Punta Conterie Art Gallery in Murano till July 19th — is the exhibition project curated by Caterina Toso, glass historian and inheritor of the Fratelli Toso Archive, which is dedicated to retracing Murano decade by decade as it was in the last century: a source of ideas, art, innovation but also an extraordinary and hardworking productive and commercial hub on an international scale.

Currently closed to the public due to the Covid-19 health emergency, Glass and design was the excuse to start a conversation with Caterina Toso about glass from the past to the present in a Murano that is evolving. A first chapter, which we plan to increase in pace over the coming weeks and months.

Vetro e disegno, ph. Valentina Cunja

Glass and design is a project focused on glass production in Murano in the last century, but which is also completely topical given the nature of the artefacts on display. Even today, in fact, the creation of artistic glass passes through a dialogue between glass-master and designer, a relationship that is not always easy, often – I noticed that you never stop emphasising this – given the lack of knowledge of the world of glass and its techniques on the part of many designers.

Ætemporary — Visiting the exhibition it is clear that the vision of the creative has led to new ways of experimentation with techniques and colours, even prompting the glass-master himself to push his luck. Some pieces on display reflectthe importance and potential of this partnership. Would you like to give some in-depth examples? For example, there are pieces that could no longer be reproduced, due to factors dictated by chance, by colours and finishes made with compounds that today can no longer be made. Some examples?

Caterina Toso — All the works selected for this exhibition are the result of the interaction between the creativity of the designer / artist / architect and the hand of the master: only by collaborating and making these two aspects interact in a smooth manner is it possible for works of art to be born. The master’s hand allows the ingenuity and imagination of the creative to take shape in the material; on the other hand the artist’s creativity suggests to the master the different and innovative use of colours, shapes, techniques by adding important elements of artistic inspiration.

I believe this principle is particularly evident in the works designed by Dino Martens for the Aureliano Toso glassworks: the use of traditional colours and techniques fused and mixed in an apparently random way – resulting in glass that is colourful, shiny, modern. Traditional elements distorted and decontextualized. Some of the colours that we can admire in these works are no longer reproducible today due to prohibitions and limitations on the use of elements and chemical compounds now classified as toxic. Many techniques that were mastered with ease, even if not completely lost, do not find equally skilled performers today. It should be emphasised that this depends not so much on a lack of talent today, more that the daily work of the past: the daily repetitiveness of gestures, manoeuvres, processes (5-6 days a week, more than 8 hours a day starting from a very early age) allowed the masters of the past to reach technical levels so high that they could easily reproduce very complex results.

Eldorado Osellaria Trombone Vetreria Aureliano Toso, Dino Martens, 1952

Æ — Moving the argument from the exhibition to today, do you think that the world of design – or if we wish, of the project – in our times can represent a plus for Murano glass?

CT — Yes, perhaps. Without wishing to generalise, I believe that contemporary Murano glass art often remains crushed under the weight of history and tradition; struggling to break free from traditional forms and styles that are stale. Design could certainly bring an influx of innovation and creativity, new ideas that would benefit artistic production. The problem lies in the lack of interaction between the creative element and that of production: the designer often does not bother to tune into the production side. Is the project actually feasible in glass? More interesting results could be achieved, artistically and – why not – also commercially, by making changes (suggested by those who know the material inside out?). The glass masters are not mere executors, but interpreters. On the other hand, glass-masters should understand that “outside” ideas are not always bad, that the cross-fertilisation of ideas from outside are physically necessary in order to survive and evolve. Respecting tradition also means allowing it to grow thanks to the experience of others.

Respecting tradition also means allowing it to grow thanks to the experience of others.

Vetro Disegno, ph. Valentina Cunja

Æ — If so, how can we bring this world closer to Murano in a constructive way?

Could residences and training workshops be a useful occasion to bridge the fundamental gap by training a new generation of creatives at ease with the world of Murano glass? If yes, is there a useful example that you would like to share?

CT — Generational change is, I think, the key term. It must be accepted that the models of the past are not eternal, on the contrary: “for a tradition to remain alive, it must be continually reinvented” (citation: Olivier Brault, Director General of the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation).

Murano should train a new generation of masters, both from Murano itself and from elsewhere: masters who are skilled with their hands, thanks to the historic local training school, but also open-minded. All-round artist-craftsmen, educated with knowledge and respect for tradition but aiming towards the future, able to engage well beyond local borders, capable of positively absorbing international ideas and influences, even the most modern and technological that should not be seen as dangerous distortions but as precious opportunities.

Æ — Actions of this type have a broader value that goes well beyond mere production by enhancing the attractive side of Murano towards a public and a cultural tourism which is what Punta Conterie aims to do, the space that is hosting Glass and design until next July. What do you think?

CT — I believe that the future of Murano, like that of our neighbour Venice, is culture. Today more than ever we have to rethink our island in terms of cultural tourism, interested in and attracted by an offer constructed around high quality.

Punta Conterie, ph. Maris Croatto

Æ — Talking about glass not exclusively with industry workers, I often have the perception that glass is not viewed as a material linked to modernity. Tradition comes first. On the one hand, it is undoubtedly good because it strengthens the long bond and the extraordinary specificity of Murano’s dominance of glass, on the other hand, however, it risks not finding a channel for dialogue with a younger or wider audience stimulated by novelty. As a native of Murano belonging to one of the great families and companies in the sector and as a great connoisseur of historical archives, what do you think?

CT — I think I answered that in my reply to the previous question.

Æ — Maybe we should invest more in strengthening the culture of contemporary glass with the opening of dedicated places, museums, galleries on the model of what happens in many other countries around the world?

CT — Of course. The art of Murano glass is in need of a 360 ° renewal: this does not mean forgetting or betraying a centuries-old tradition, but it means taking our very rich cultural background and making it usable in a modern, interactive way. It must shake off the dust and the odour of mothballs, by conveying its history in a way that reaches new generations who will have the task of carrying on the tradition and the art of glass in the future.

Æ — Could bringing back — as Lino Tagliapietra, the most important glass artist well-known throughout the world, believes — the Glass Bienniale be useful to bring attention back to artistic glass?

CT — Any inclusive and representative event that gives space to tradition, modernity, the interaction between local and international schools. That gives space to the “big” as well as to the young people who are emerging. Where equal attention is given to the role of the maker – to the glass-master – and to the creative and planning part – the designer.

_________________

* Glass and design, the creative process in the historic Murano glass factories of the 20th century * presentsdesigns and more than 50 artistic glass objects made in the years between 1910 and the 1980s coming, in addition to the archival material on display, from the glassworks of from the glassworks of Fratelli Toso, Barovier&Toso, SALIR, A.Ve.M and Galliano Ferro, and from the Giorgio Cini Foundation and the Centro Studi Vetro (Centre for Glass Studies) with the designs of Venini, Seguso Vetri d’Arte and Aureliano Toso. The works, all original glass creations, come from important Italian and foreign private collections, including the German collection of Lutz H. Holz and from the heirs of Vistosi.

Glass and design